SHARKS OF NEW JERSEY

Sharks Of The Jersey Shore!

YES!

Sharks really do call the Jersey Shore home!

A variety of sharks, from threshers to makos, to bulls to blues, to whites to hammerheads, to dogfish and even occasionally a whale shark (the largest fish in the ocean!), and so many more can be found either seasonally or year-round along the Jersey Shore.

For a long time, a lot of energy from books, movies, television shows and magazine articles has been spent by people declaring sharks as dangerous sea monsters and we need to be afraid of sharks. Yet, it’s sharks that need to be afraid of people. On average, sharks kill around or less than 10 people worldwide. In contrast, an estimated 100 million sharks are killed every year around the world for food or body parts or as bycatch, a number that far exceeds what many shark populations can endure.

Instead or being afraid of sharks we need to understand the ecology and biology of sharks better, and respect and protect sharks for the important role they play in keeping our aquatic ecosystems and habitats functioning and viable. Like every other sentient species on this planet, sharks have intrinsic value and a right to exist.

WE NEED TO PROTECT SHARKS IN NEW JERSEY!

Yet, the Atlantic spiny dogfish is classified in the IUCN Red List of threatened species as Vulnerable globally and Critically endangered in the Northeast Atlantic, meaning stocks around Europe have decreased by at least 95%. While the EU previously had a zero-tolerance policy for targeted spiny dogfish fishing in the Northeast Atlantic to facilitate stock recovery, as of April 1, 2023, UK-registered fishing vessels are now allowed to target spiny dogfish in both UK and EU waters following advice from the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) that the stock is slowly recovering.

Even still, decades of overfishing, poor management, and the desire for quick profit has caused the spiny dogfish population to collapse around the European Union and the United Kingdom. This is due to the taste by many people in Northern Europe for spiny dogfish, also known as rock salmon, saumonette, and zeepaling. There is little consumer demand for spiny dogfish in the United States, but it is commonly used in Europe as the fish in 'fish and chips’ dishes and other meals.

Many fish and chip shops in England today sell spiny dogfish as the main ingredient. The French use it in stews and soups and Italians import dogfish as well. Italian recipes will reference dogfish as “Huss”, or Palombo. In USA fisheries, the belly flaps are cut out, the fins removed, and the body is skinned leaving a white carcass or ‘back’ which is generally exported to Europe, particularly: France, Germany, Belgium, the UK, and Italy. Belly flaps are exported solely to Germany where they are smoked and used to prepare ‘Schillerlocken,’ a popular beer garden snack that calls for smoked meat or in this case smoked dogfish belly flaps. Fins are frozen and exported to primarily Thailand, where they are re-processed and re-distributed into the broader Asian fish market.

To satisfy this great demand for dogfish, commercial fishermen in Canada and the United States will catch Atlantic spiny dogfish around the Grand Banks of the Northwest Atlantic and nearby waters to import and supply Northern Europe's taste. This includes along the Jersey Shore where there is active fishery for Atlantic spiny dogfish out of Barnegat Light, NJ. Commercial fishermen here can catch up to 900,000 pounds per year of spiny dogfish. The spiny dogfish fishery in the United States operates year-round from May 1 through April 30.

Over the last 20 years, the United States has become the major supplier of spiny dogfish to the European Union. The US accounts for over 90% of the global supply of dogfish, and the European Union represents over 90% of the global demand.

Even though management policies put in place by Canada and the United States show that the Atlantic spiny dogfish stock at and around the Grand Banks is not currently overfished, in 2023 federal fishery regulators slashed the coast-wide commercial quota in the United States for spiny dogfish by nearly 60%, from just over 29 million pounds to 12 million pounds due to declining populations. Proposed 2025 specifications would decrease the acceptable biological catch by another 2 percent, and the coast-wide commercial quota by 18 percent, compared to fishing year 2024.

Nevertheless, how much longer can intense commercial fishing continue before the Atlantic spiny dogfish becomes endangered in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean?

These fish have the longest gestation period of all sharks, even rivaling the elephant’s gestation period (on average 22 months). Female Atlantic spiny dogfish have between two and 12 eggs per spawning season. The eggs are fertilized internally and, after a gestation period of 18 to 24 months, for a total of 2 years spent in the womb, females bear live young.

An average of only 6 pups are born at a time, with up to 12 or maybe 15 pups per year.

In New Jersey we are still catching 900,000 pounds a year! Spiny dogfish, typically weigh between 7 to 10 pounds.

This means in New Jersey alone we are catching around 90,000 to 120,000 spiny dogfish per year.

There is absolutely nothing sustainable about having a shark fishery in New Jersey!!

STOP THE ATLANTIC SPINY DOGFISH FISHERY!

Due to overfishing, spiny dogfish are listed as a vulnerable species by the IUCN

Atlantic Spiny dogfish is used as a substitute for cod in the popular British dish "fish and chips", particularly in Europe, where it's often marketed under names like "rock salmon" or "huss". The dogfish used in European fish and chips dishes often comes from fisheries in the United States, including Barnegat Light, New Jersey.

STOP

THE ATLANTIC SPINY DOGFISH FISHERY IN NEW JERSEY!

Authors Daniel C. Abel and R. Dean Grubbs in their book, Shark Biology and Conservation, published by John Hopkins University Press in 2020, tells us that the Northwest Atlantic Ocean, specifically around the Grand Banks of Newfoundland and adjacent waters, are where the greatest biomass or where the most numerically abundant sharks species in the world lives - the Atlantic Spiny Dogfish (Squalus acanthias).

PROTECT SHARK NURSERIES

AROUND THE JERSEY SHORE.

New Jersey and surrounding waters are home to several shark nursery areas where juvenile sharks are more commonly encountered or where juvenile sharks have a tendency to remain or return to the area for extended periods to grow, feed, and try to stay hidden from potential predators.

In 2018, a great white shark nursery was confirmed in the New York - New Jersey Bight. The bight extends northeasterly from Cape May Inlet in New Jersey to Montauk Point on the eastern tip of Long Island. This is an important reason why both many adult female and juvenile white sharks are commonly found near the Jersey Shore and within the New York - New Jersey Bight.

In 2016, scientists from the New York Aquarium confirmed a sand tiger shark nursery off the south shore of Long Island in the tidal waters of Great South Bay. Sandbar sharks have been found to use Barnegat Bay and Delaware Bay as nursery areas. Tagging of sharks shows that both sandbar and sand tiger sharks are common species of large sharks found along the Jersey Shore during the summer, most likely due to the location of nearby related nursery areas.

There is also a smooth dogfish shark nursery in many New Jersey estuaries or shallow tidal waters, particularly Great Bay and Little Egg Harbor, where pups feed and grow.

WHY ARE SHARKS IMPORTANT TO PROTECT?

Sharks are vital for healthy oceans as apex predators, maintaining the balance of marine ecosystems by regulating prey populations, supporting biodiversity, and ensuring the health of coral reefs and other aquatic habitats.

Medical

Sharks have been around for over 400 million years. During this time, sharks have developed remarkable ways to survive, including immune systems that can resist cancers and other diseases. Medical researchers are studying sharks to see if humans are able to treat people with cancer from different shark compounds.

Current biomedical benefits of sharks to humans include: Diabetic foot ulcers are treated with a some degree of shark cartilage. The compound chondroitin sulfate derived from shark cartilage may slow the progression of osteoarthritis. The compound squalamine, which is found in the liver and stomachs of some sharks, appears to prevent the buildup of a lethal protein associated with Parkinson’s disease and dementia. Shark liver oil is one of the ingredients in the anti-hemorrhoidal cream - Preparation H.

Maintaining Biodiversity:

By controlling prey populations, sharks contribute to the overall health and biodiversity of marine ecosystems to make sure no one species has control over an ecosystem.

Supporting Coral Reefs:

Sharks play a crucial role in maintaining healthy coral reefs by preying on fish that could otherwise overgraze the reefs, leading to their degradation.

Healthy Fish Populations:

Sharks help keep fish populations healthy by preying on sick or weak individuals, which prevents the spread of disease and maintains the overall health of the fish community.

Carbon Sink:

Sharks, along with other marine animals, can store a significant amount of carbon in their bodies, which helps to keep carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and mitigate climate change.

Economic Benefits:

Sharks are important for local economies through ecotourism and recreational activities like shark diving, which generate revenue for local communities and promote conservation awareness.

Keystone Species:

Sharks are considered keystone species, meaning their removal from the ecosystem would have a disproportionately large impact on the entire food web and the health of the ocean.

Get submerged in the amazing world of sharks! Your expert host, award-winning marine biologist Dr. David Shiffman, will show you how—and why—we should protect these mysterious, misunderstood guardians of the ocean.

Johns Hopkins University Press (May 24, 2022)

Apex Predators and Ecosystem Balance:

Many sharks are apex predators. This means they are at the top of an aquatic food chain and help to keep an ecosystem healthy by going after prey that is slow or sick. The healthiest fish often survive to breed and contribute to a stronger and hardier gene pool in an ocean or estuary.

Sharks also have a varied diet. This helps to maintain a healthy aquatic food chain as they feed on the most abundant species to avoid the formation of "invasions" of species that could monopolize an entire ecosystem.

Even those sharks that are smaller and may not be an apex predator still help to preserve an ecosystem’s biodiversity either by being prey or by preventing species from overpopulation.

Why Are Sharks Unlike Any Other Fish?

Like rays and skates, sharks fall into a subclass of fish called elasmobranchii. These types of fish have skeletons made from cartilage, not bone, and have five to seven gill slits on each side of their heads (most other fish have only one gill slit on each side), which they use to filter oxygen from the water.

Based on fossilized teeth and scales, scientists believe sharks have been around for over 400 million years—long before the dinosaurs. Sharks have lived through multiple mass extinction events and have survived long past many ancient rival fish species.

Over time, sharks have evolved and developed a unique external anatomy and several distinguishing features to make them a popular top predator in an ocean or estuary and a truly extraordinary fish. There are over 453 species of sharks currently living around the world’s oceans that come in a variety of colors (goblin sharks can be a bright pink color) and sizes. The smallest shark is the dwarf lantern shark, which is about the size of a human hand, while the largest shark is the whale shark, it can be up to 40 feet long.

Sharks are one of the most evolutionarily successful species to ever live. There is no other fish in the sea that has so many books, magazine articles, web sites, videos, movies, documentaries, and a whole week on television devoted to learning more about sharks.

The following are just a few of the unique properties that make sharks remarkable fish and worthy of further study and protection; and even more webpages and documentary shows.

CARTILAGE

Unlike most other fish, all sharks have cartilage skeletons instead of bones. This cartilage skeleton is what allows sharks to bend, move, and stay buoyant. Otherwise, sharks would sink because of the lack of a swimming bladder.SHARK SKIN

The skin or outer covering of a shark is rough as it has small scales similar to teeth, called dermal denticles. The aligned structure of these denticles is useful for channeling water over the body and minimizing frictional resistance, making it easier to swim long distances and save energy. Dermal denticles also help to protect a shark’s skin from injuries.

JAWS

The jaws of many species of sharks are not attached to the skull. Instead, the jaws move as a separate body part. The upper and the lower jaw can work independently without the other. This versatility provides sharks with a very powerful weapon. They are able to extend further outward their sharp teeth to grab onto prey fiercely.

SHARK LIVER.

A shark’s liver can store oil in it for long periods of time. Sharks can survive with this oil reserve for weeks, months, or even a year before seeking another meal. A shark never depletes the stored oil in its liver. and will return to foraging for food once the level of oil in their liver gets decreases.

SHARK TEETH

Many species of sharks have several rows of teeth that are extremely sharp as most sharks are meat eaters. When a shark loses a tooth from ripping through flesh and bones, a new tooth from the back row moves forward to replace it. On average, a shark can lose the entire row of front teeth every couple of weeks to a month; and use around 30,000 teeth in its lifetime. No wonder why there are so many shark teeth to be found around the world.

The ampullae of Lorenzini pores on the face of a sandbar shark.

SMELL

Sharks have amazing noses. As a shark swims, water passes into its nostrils and across sensory cells that are able to detect relatively small amounts of a chemical signal in the water. A shark’s two nostrils can also detect smells separately to determine from which direction they originated, allowing them to smell in stereo!

The Ampullae of Lorenzini

Sharks have a “sixth sense” that allows them to detect the small electric fields that all animals create when their muscles move and contract. The small pores on a shark’s head are full of special cells called ampullae of Lorenzini. These cells are filled with a jelly-substance that conduct electric charges received from ions, like sodium and chlorine, which are found in salt water. When a fish moves its muscle to swim or when one is wounded, it sends out a large electrical signal that will attract a shark.

ARE SHARKS ENDANGERED?

YES!

BUT this is what we only know for sure! Most shark fisheries around the world are virtually unmonitored and completely unmanaged. Take for example recent data from NOAA Fisheries’ recent stock assessment of 64 commercial and recreational shark stocks in the United States.

It shows:

40 (62.5%) stocks have “unknown” overfished/fishing status

12 (18.75%) are not overfished or experiencing overfishing

4 (6.25%) are overfished or experiencing overfishing

8 (12.5%) have mixed status information.

More than 60% of the assessed fished shark stocks in the North-West Atlantic ocean (including along the Jersey Shore) are completely unknown. No one is quite sure if a majority of fished shark species found along the Jersey Shore and in nearby waters are currently overfished or being overfished. Furthermore, most shark fisheries around the world are virtually unmonitored and unmanaged.

Although population data for many species of shark is insufficient or outdated, quite a few species of sharks are vulnerable and endangered, including many shark species that are encountered along the Jersey Shore. According to research done by NOAA Fisheries in the past 30 years in the North-West Atlantic ocean, the following shark populations are in trouble:

Hammerhead sharks - 89% decline since 1986

White sharks - 79% decline (no date specified)

Tiger sharks - 65% decline since 1986

Coastal species - 61% decline since 1992

Thresher sharks - 80% decline (no date specified)

Blue sharks - 60% decline (no date specified)

Why Are Many Species of Sharks In Decline?

SHARKS DON'T REPRODUCE LIKE OTHER FISH!

Sharks are more like people!

Many species of sharks reproduce through internal fertilization. Sharks mature slowly, often maturing in their teens. Sharks bear few young, and do not reproduce every year.

These characteristics make sharks very susceptible to overfishing!

Increasing fishing pressure is causing shark populations to decline because the life history of this fish makes it difficult for shark populations to increase sufficiently and rapidly to meet demand and replace those sharks removed by fisheries.

SHARKS ARE SLOW GROWING & LATE TO MATURE - Many sharks are killed before they’ve produced offspring.

SHARKS HAVE LONG PREGNANCIES - averaging between 9-12 months.

SHARKS PRODUCE FEW YOUNG - varying from 2 pups for the Bigeye Thresher and up to 135 for the Blue Shark. This is unlike reproduction methods of many bony-fish species, such as striped bass, bluefish, or summer flounder. A single female bony-fish species typically releases hundreds to millions of eggs once a year during her lifetime.

SHARKS MAY NOT REPRODUCE EVERY YEAR - So much maternal care and energy goes into reproduction that quite a few female species of sharks have a resting phase of 1 to 2 years to rebuild energy reserves.

Some sharks and rays are viviparous (will keep the eggs in their uterus) others oviparous (will lay eggs).

Oviparous reproduction is used by about 30 % of sharks and rays in the world. After mating they will lay eggs covered by a leathery case on the sea floor or attached to reefs. The young will develop inside this egg case and when the food supply (yolk) is finished the young shark will move through a slit in the case and swim away.

Viviparous reproduction is when sharks and rays give birth to live young, just like mammals. In some species of sharks the eggs will hatch inside the mother and the pups are born alive. In a few species the pups doesn’t only use the egg yolk for nourishment but also unfertilized eggs the mother produce to feed her young.

BYCATCH

Sharks are frequently caught as bycatch—which means that, while fishermen were trying to catch a different kind of fish or shellfish like scallops, they accidentally caught sharks in their nets too. Because the nets for commercial fishing are so large in size, by the time fishermen get to species that are caught as bycatch, the poor animals are often dead.

In addition to bycatch, there is active fishery in New Jersey for Atlantic spiny dogfish and winter skates. Gillnets are commonly used to catch dogfish and skates. The nets run several hundred feet in length. Their depth may be from ten to forty feet. They intercept fish as bycatch while they are swimming, either along the shore or as they move in and out. Depending on the species sought, gillnets can be fished on the bottom, at the surface or anywhere in the water column. The nets often catch fish by the gills, hence their name.

Because sharks grow slowly, are late to mature, and produce few young, they are especially vulnerable to overfishing and slow to recover from depletion. Some populations of shark species are in decline because of bycatch and excessive human fishing. Other shark species are in decline due to people killing sharks for their fins, sports, medicine, meals or just because they are afraid of sharks. Bits of shark meat can also be found in fast food and in pet food. The value and the demand for shark products is rising, which is resulting in increasing pressure and stress on shark populations.

Quite a few human actions are dramatically reducing the population of shark species and have driven a number of populations closer to extinction. Tens of millions of sharks are killed each year and many populations continue to decline at an alarming rate.

STOP EATING SHARK FIN SOUP!

Image from Wikipedia. Shark fin soup is an ancient Asian dish that’s said to signify prosperity. It’s so sought-after in many Asian markets (including Chinatowns in both New York City and San Francisco) that a single bowl can go for up to $100. Putting a pretty price on an individual shark.

Continued demand for shark fin soup, dumplings, and other shark fin dishes served in restaurants around the world today perpetuates the practice of finning, resulting in an estimated 73 million sharks being killed each year for their fins alone according to the Animal Welfare Institute.

Men cutting off shark fins - shark finning in Indonesia.

Shark fin soup does not make you healthier or live longer. In fact, several neurogenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), have been linked to eating shark fin soup. All shark fin soup does is drive sharks to extinction!

When sharks are captured by people for food, the sharks are often finned alive, meaning their fins are cut off while the shark is still alive. The sharks are rendered immobile and often released back into the water, leaving them to either sink to the bottom of the ocean and suffocate to death or be eaten alive by other predators. It is a cruel and senseless way to die. Please stop eating shark fin soup!

What is being done to Save Sharks?

Shark populations have been in trouble for decades largely due to illegal fishing and overfishing. Since 2000, shark finning has been banned in the United States when the Shark Finning Prohibition Act was signed into law. The law stated that fishing vessels could not transport or possess shark fins without the corresponding shark body within 200 miles of U.S. shore. But regulators found the law was difficult to enforce. As a result, in January 2011, President Barack Obama signed the Shark Conservation Act into law to close the loopholes. Specifically, the new law prohibits any boat to carry shark fins without the corresponding number and weight of carcasses, and all sharks must be brought to port with their fins attached. The “fins attached” regulation applies to all sharks in U.S. waters except for the smooth dogfish, which is commercially fished under NOAA Fisheries regulations on the East Coast of the U.S..

Yet, the Shark Conservation Act doesn’t manage the trade of shark fins once they are caught. Hawaii was the first U.S. state to ban the possession, sale and trade of shark fins, and was quickly followed by a handful of other states.

As of January 2020, 13 U.S. states and 3 U.S. territories have banned the sale and possession of shark fins: American Samoa, California, Delaware, Guam, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Northern Mariana Islands, Oregon, Rhode Island, Texas, Washington.

In addition to finning bans in the United States, shark populations are managed under the National Marine Fisheries Service in regional fisheries management plans. These plans reflect the results of research, population assessments and work with commercial and recreational fishermen. Additionally, two populations of scalloped hammerhead sharks were listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act in July 2014, making them the first sharks protected under the law.

What can you do to help protect sharks along the Jersey Shore?

Do Not Eat Shark Body Parts! Shark meat, shark fin soup, and folk medicine made from shark cartilage should all be avoided!

But to really save sharks you need to go one step further. Sometimes it’s not always easy. Oils from shark liver and shark meat can be found in a range of products from pet food to health & nutrition pills. For example, a 2020 study, analyzed 87 pet food products from 12 different brands for traces of shark DNA. All the pet foods tested were generically labeled with ingredients such as “ocean fish” and gave no indication of containing meat from sharks, BUT of the 87 different pet foods analyzed, 21 pet food products were identified as containing shark DNA. The two shark species identified in these pet foods were the shortfin mako shark and the blacktip shark. Please before consuming any product, positively make sure it does not contain any shark body parts, or better yet, just avoid that product and find an environmentally friendly alternative. In addition, shark meat can make your or your pet sick, as shark meat has been shown to carry extremely high levels of toxic metals such as mercury that far exceed what is allowable for human consumption.

Keep sharks out of your cosmetics! The majority of Squalene and Squalane comes from shark liver oil. Never use any products (including makeup, wrinkle creams, lotions, and deodorants) that contain Squalene unless it specifically states ‘100% plant-derived,’ or ‘vegetable based’ or “vegetable origins”.

Speak Out When You See Abuse! If you see someone abusing sharks, speak out! Whether they are poking and prodding them or illegally fishing them, tell the authorities at NOAA Fisheries what you’ve seen. To report a violation - call (800) 853-1964. The number is available 24/7.

Reduce Your Seafood Consumption! Commercial fishing has shown to negatively impact sharks in several ways. For example, it reduces the populations of their food sources, and sharks are often killed as bycatch or a byproduct of commercial fishing from getting caught in nets or in line. Do not eat shark meat! Shark meat has been found to contain high levels of toxins and metals including mercury. Instead of eating seafood, go Vegan or Vegetarian!

Learn As Much As You Can About Sharks! By educating yourself on issues concerning the preservation of sharks, you can find effective ways to help. You can also help enlighten others about sharks and inspire more people to get involved. Spread the word on social media as well.

“Sharks are beautiful animals, and if you're lucky enough to see lots of them, that means you're in a healthy ocean. You should be afraid if you are in the ocean and don't see sharks.”

~ Sylvia Earle, an American marine biologist, oceanographer, explorer, author, and lecturer

SHARK FIELD GUIDE

The following is a short list of some of the most common species of sharks to be found along the Jersey Shore either year-round or seasonally. For more in-depth information about sharks, please visit the NOAA Fisheries webpage about Sharks in Atlantic Coastal Waters and the Florida Museum of Natural History shark webpage.

Smooth “Hound” Dogfish (Mustelus canis)

The most abundant species of shark along the Jersey Shore. The shark is actually a member of the Houndshark family and not a true dogfish.

Distribution: Globally, found in the Northwest Atlantic from Canada to Argentina. Locally from Massachusetts to Florida, including Gulf of Mexico.

Habitat: Coastal bays and nearshore waters usually less than 60 feet but can be found down to 660 feet or deeper near the Continental shelf. It prefers mud and sandy bottoms.

Behavior: Very active shark, especially at night when it forages for food.

Migration: Local population migrates inshore in the summer and offshore in the winter to the Continental shelf.

Reproduction: Viviparous. Females bears 4 to 20 pups after ten month gestation. Juveniles mature in one to two years.

Sizes: Juveniles are born 12 inches to 16 inches. Matures to about 2.6 feet for males and 3 feet for females, with maximum length at 5 feet.

Notes: According to the Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey: “The smooth dogfish currently has no federal or New Jersey state conservation status. They are abundant and are often caught by fishermen both from shore and offshore. Because of the frequency with which they are caught, many are often intentionally killed as “junk fish” or for consuming bait intended for other fish.”

The common name "dogfish" originated from fishermen who described these fish as chasing smaller fish in large dog-like "packs," according to a species profile of the fish from the Florida Museum of Natural History.

The smooth dogfish poses no threat to humans due to its small size and small blunt, pavement-like teeth.

Atlantic Spiny Dogfish (Squalus acanthias)

The most abundant species of shark in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean as far as biomass. Yet, due to overfishing and the spiny dogfish being caught as bycatch, the global population of spiny dogfish is considered vulnerable and is on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List of threatened species.

Distribution: Globally, almost world-wide except tropics and near poles. Little or no mixing between northern and southern hemisphere populations and limited genetic mixing between some stocks with overlapping range and feeding grounds, but different migrations patters. Locally from Greenland to Florida and Cuba.

Habitat: Coastal and offshore ocean waters. Surface waters to 3,000 feet. Usually near bottom in 43 to 52 degrees F on the Continental shelf. Often on soft sediments in bays and estuaries where most nursery areas occur.

Behavior: Mainly lives near surface of the sea. Sometimes solitary or schooling with other small sharks, often forming large dense feeding aggregations on rich feeding grounds. Segregates by size and sex into packs or schools of small juveniles (both sexes), mature males, larger immature females, and large pregnant females. Spiny dogfish are known for their highly localized very large schools.

Migration: Slow swimmer, but many undertake long distance seasonal migrations north to south or deep to shallow waters as water temperatures changes. Some spiny dogfish migrate more than 5,000 miles.Some populations are year-round residents. Long distance movements reported from tag returns of at least one dogfish that migrated over 994 miles in the northwest Atlantic Ocean.

Reproduction: Ovoviviparous: producing young by means of eggs which are hatched within the body of the female, similar to snakes. Males reach maturity after about 11 years; females reach maturity after 18 to 21 years. In winter, pairs will mate in offshore waters. Once the eggs are fertilized, a protective shell forms and protects the embryo. After 4 to 6 months, the shells are shed and the young gestate for 18 to 20 more months, for a total of 2 years spent in the womb. An average of 6 pups are born at a time, but can be up to 12 pups. These fish have the longest gestation period of all sharks, even rivaling the elephant’s gestation period of up to 22 months.

Sizes: Extremely long-lived (30 to 45 years, sometimes up to 70 to 100 years), late-maturing (10 to 25 years) and slow-growing. Born 7 to 13 inches. Matures 20 to 40 inches for males and 25 to 48 inches for females with maximum length reported at over 6 feet.

Notes: According to Wikipedia: Once the most abundant shark species in the world, populations of Squalus acanthias have declined significantly. They are classified in the IUCN Red List of threatened species as Vulnerable globally and Critically endangered in the Northeast Atlantic, meaning stocks around Europe have decreased by at least 95%. This is a direct result of overfishing to supply northern Europe's taste for rock salmon, saumonette, and zeepaling. Despite these alarming figures, very few management or conservation measures are in place for Squalus acanthias. In 2010, Greenpeace International added the spiny dogfish to its seafood red list.

Sand Tiger Shark (Carcharias taurus)

Sand tiger sharks are a threatened species. They have one of the lowest reproductive rates of any shark. Overfishing is a major threat to their survival.

Distribution: Warm temperate and tropical Atlantic. Locally from the Gulf of Maine to Florida including the Gulf of Mexico, Bahamas and Bermuda.

Habitat: Mostly shallow coastal waters from shallow bays and the surf zone to the outer shelf. Generally bottom dwelling.

Behavior: A slow but strong swimmer, more active at night. Air swallowed at the surface and held in stomach provides neutral buoyancy, enabling the shark to hover in the water.

Migration: Some are highly migratory, moving to cooler waters northward in the summer.

Reproduction: Viviparous. Mating occurs around the months of August and December in the northern hemisphere. After a lengthy labor, the female gives birth to one 3.3 foot long, fully independent offspring. The gestation period is approximately eight to twelve months. The sharks give birth only every second or third year, resulting in an overall mean reproductive rate of less than one pup per year, one of the lowest reproductive rates for sharks.

Size: Males reach 6.2 feet in length. Females reach 7.2 feet long.

Notes: The sand tiger is often associated with being vicious or deadly, due to its relatively large size and sharp, protruding teeth that point outward from its jaws; however, these sharks are quite docile, and are not a threat to humans. Their mouths are not large enough to cause a human fatality.

Sand Tiger sharks due to their vicious appearance and docile nature, are popular in aquariums. However, sand tiger sharks in aquariums face several challenges, including spinal deformities due to constrained swimming spaces and potential reproductive difficulties, as well as issues with nutritional deficiencies and stress from captivity. Aquarium reproduction is difficult, with only 15 live births ever recorded.

Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus)

The basking shark is the second-largest living shark, after the whale shark, and one of three plankton-eating shark species, along with the whale shark and megamouth shark.

Distribution: World-wide, cold to warm temperate waters. Locally from Newfoundland, Canada to Florida. Frequently seen along the Mid-Atlantic coast in spring to the coast of New England, and Gulf of Maine in summer.

Habitat: Coastal and offshore, sometimes enters large bays and estuaries.

Behavior: Often observed feeding on plankton on the surface of the water. Moves slowly with open mouth.

Migration: Highly migratory. Basking sharks have been shown from satellite tracking to overwinter in both the Continental shelf (less than 660 feet) and deeper waters. One tagged shark traveled from Cape Cod, MA to near the mouth of the Amazon River.

Reproduction: Ovoviviparous. Mating is thought to occur in early summer and birthing in late summer. Gestation is thought to span over a year (perhaps two to three years), with a small, though unknown, number of young born fully developed. Only one pregnant female is known to have been caught; and she was carrying six unborn young.

Size: Born 4 feet 11 inches to 6 ft 7 inches. Adults 15 to 20 feet.

Notes: The shark’s name comes from its habit of feeding at the surface, appearing to be basking in the warm water. The IUCN Red List indicates the Basking shark is an endangered species.

Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus)

Whale sharks are the largest known fish in the world. The largest confirmed individual had a length of 62 feet.

Distribution: Circumglobal. All tropical and warm temperate seas, except the Mediterranean. Locally from the coast of New England & Long Island to central Brazil, including the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea.

Habitat: Coastal and offshore. Most common in water temperatures from 68 degrees F to 77 degrees F.

Behavior: The whale shark is a filter feeder. It feeds on plankton including copepods, krill, fish eggs, and small nektonic life, such as small squid or fish.

Migration: Highly migratory. It usually roams between 30°N and 35°S where water temperatures are higher than 70 °F) but have been spotted as far north as the Bay of Fundy, in Canada.

Reproduction: Ovoviviparous. Growth, longevity, and reproduction of the whale shark are poorly understood. A female from Taiwan had around 300 pups in her uterus. Evidence indicates the pups are not all born at once, but rather the female retains sperm from one mating and produces a steady stream of pups over a prolonged period.

Size: Born 1.2 feet to 2.1 feet. Adults average to about 40 feet, but can grow up to more than 60 feet.

Notes: There is currently no robust estimate of the global whale shark population. The species is considered endangered by the IUCN due to the impacts of fisheries, by-catch losses, and vessel strikes, combined with its long lifespan and late maturation.

Atlantic Common Thresher Shark (Alopias vulpinus)

Atlantic or common thresher sharks are familiar fish in New York Harbor and along the Jersey Shore. Thresher sharks use their long tails to herd and stun prey including small fish.

Behavior: Herds and stuns small fish with its tail, sometimes cooperatively with other threshers. Some threshers may leap out of the water.

Migration: Migrates seasonally along the coast.

Reproduction: Common thresher sharks mate in late summer. Ovoviviparous: producing young by means of eggs which are hatched within the body of the female, similar to snakes. Two to six pups (usually four). Females bear live, fully developed young after a long gestation period (9 months), and only have a few pups.

Sizes: Born 3.75 feet to 5.25 feet. Males sexually mature when they’re 8 to 11 feet long and 3 to 6 years old. Females are able to reproduce when they’re 8 to 9 feet long and 4 to 5 years of age. Adults can reach up to 20 feet. The caudal fin is sickle-shaped and is about 50 percent of the total body length.

Notes: Common thresher sharks are known to live to at least 15 years and their maximum lifespan has been estimated to be 45–50 years.

According to NOAA fisheries: “Atlantic common thresher sharks have never been assessed and the population status is unknown.”

Furthermore NOAA Fisheries states: Common thresher sharks are aggressive predators that feed near the top of the food chain on schooling fish such as herring and menhaden and occasionally on squid and seabirds.

They are named for their long, scythe-like tail, which is used to stun fish before preying on them.

Adult common thresher sharks have few predators, but younger, smaller ones may fall prey to larger sharks.

Threshers sharks have small mouths and pose little threat to humans except for getting hit by their strong tail which can be dangerous.

Shortfin Mako (Isurus oxyrinchus)

The shortfin mako (also known as a blue pointer or bonito shark) is currently classified as Endangered by the IUCN, having been up-listed from Vulnerable in 2019 and Near-Threatened in 2007. The species is being targeted by both sport and commercial fisheries, and there is a substantial proportion of bycatch in driftnet fisheries for other species.

Image from Wikipedia With attack speeds between 25 to 60 miles per hour (similar to a speedboat), the shortfin mako is the fastest shark and is one of the fastest fishes on the planet. They are so fast, this fish even made into the Guinness World Records. The normal cruising rate of a typical shark is around 2 miles/hour during the day. Great white sharks can swim at speeds of around 16 mph for short bursts.

Distribution: World-wide in all temperate and tropical waters Locally found from Newfoundland, Canada to Brazil, including the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. Common in Northwest Atlantic Ocean.

The bite of a shortfin mako shark is exceptionally strong; the current record for the strongest bite measured for any shark belongs to a shortfin mako that was recorded at Mayor Island in New Zealand in 2020. The shark had been coaxed into biting a custom-made "bite meter" as part of an experiment to measure mako bite force. The strongest bite recorded during the experiment was roughly 3,000 lbs. of force.

Habitat: Offshore from surface to about 500 feet generally in waters with a temperature greater than 61 degrees F.

Behavior: Possibly the fastest shark in the world. It can jump high out of the water in pursuit of prey. Like other lamnid sharks, the shortfin mako shark has a heat-exchange circulatory system that allows the shark to be 7–10 °F warmer than the surrounding water. This system enables this shark to maintain a stable, very high level of activity, giving it an advantage over cold-blooded prey.

Migration: Highly migratory.

Reproduction: The shortfin mako shark is ovoviviparous, giving birth to live young. Developing embryos feed on unfertilized eggs within the uterus during the 15 to 18 month gestation period. They do not engage in sibling cannibalism. The four to 18 surviving young are born live in the late winter and early spring at a length of about 28 inches. Shortfin mako sharks bear young on average every three years.

Sizes: Mature males 6 to 7 feet. Mature females 9 to 10 feet and up to 13 feet.

Notes: Life span is perhaps around 30 to 35 years. Of all studied sharks, the shortfin mako has one of the largest brain-to-body ratios. The shortfin mako shark feeds mainly upon cephalopods and bony fish including mackerels, tunas, bonitos, and swordfish, but it may also eat other sharks, porpoises and dolphins, sea turtles, and seabirds.

Porbeagle (Lamna nasus)

The Porbeagle Shark is a cold water shark that resembles a smaller Great White. It can live in colder water habitats compared to other sharks. It is common from Newfoundland to Massachusetts. Seasonally to New Jersey in the winter or spring.

Distribution: In cool waters from 33.8 degrees F to 65.4 degrees F.

Habitat: Offshore. Continental shelf waters from surface to bottom to 1,200 feet. Juveniles closer to the shore.

Behavior: Inquisitive. May approach boats and divers but not dangerous. The porbeagle is an opportunistic hunter that preys mainly on bony fishes and cephalopods throughout the water column, including the bottom.

Migration: Moves to shore in summer, winter offshore in deeper water.

Reproduction: Ovoviviparity. Mating takes place mainly between September and November, though females with fresh mating scars have been reported as late as January off the Shetland Islands. The male bites at the female's pectoral fins, gill region, and flanks while courting and to hold on for copulation. Two mating grounds are known for western North Atlantic porbeagles, one off Newfoundland and the other on Georges Bank in the Gulf of Maine. The litter size is typically four; on rare occasions, a litter may contain as few as one or as many as five pups. The gestation period is 8–9 months.

Sizes: Born 1.9 feet to 2.6 feet. It typically reaches 8.2 feet in length, up to 9.8 feet, and a weight of 298 lbs.

Notes: The porbeagle is a species of mackerel shark in the family Lamnidae, distributed widely in the cold and temperate marine waters of the North Atlantic and Southern Hemisphere. In the North Pacific, its ecological equivalent is the closely related salmon shark. In 2004, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada listed the porbeagle as endangered.

Great White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias)

The “Great” white shark is one the best examples of an apex predator or top predator, which is an animal that is at the top of a food chain, without or very few natural predators when an adult. White sharks are regular visitors to the Jersey Shore, especially during the summer. For example, Miss May, a 10-foot, 800-pound tagged great white shark visited the Jersey Shore in summer 2020. Follow other tagged white sharks for yourself at the OCEARCH Shark Tracker website.

Distribution: Almost world-wide. Locally found from Newfoundland, Canada and the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Florida, Cuba, Bahamas, and the Gulf of Mexico.

Habitat: Most abundant near land and in shallow waters. Found offshore along the Continental shelf to at least 1,200 feet.

Behavior: Inquisitive and intelligent with a highly complex social behavior. Great white sharks are carnivorous and prey upon fish (e.g. tuna, rays, other sharks), cetaceans (i.e., dolphins, porpoises, whales), pinnipeds (e.g. seals), sea turtles, and seabirds. Juvenile white sharks predominantly prey on fish.

Migration: Highly migratory fish.

Reproduction: Little is known about the great white shark's mating habits, and mating behavior has not been observed in this species until 1997 and properly documented in 2020. Great white sharks were previously thought to reach sexual maturity at around 15 years of age, but are now believed to take far longer; male great white sharks reach sexual maturity at age 26, while females take 33 years to reach sexual maturity. Litters of two to ten pups. Gestation is around 12 months at two to three year intervals.

Sizes: Born 3.6 feet to 5.2 feet. Adult males measure 11 to 13 feet, and adult females measure 15 to 16 feet on average to about 20 feet.

Notes: Very effective predator, may breach out of the water when attacking prey. White sharks are warm-blooded and can maintain a constant high body temperature even in cold water. The IUCN notes that very little is known about the actual population status of the great white shark, but as it appears uncommon compared to other widely distributed species, it is considered vulnerable.

A sign warns visitors of sharks at Cape Cod, MA

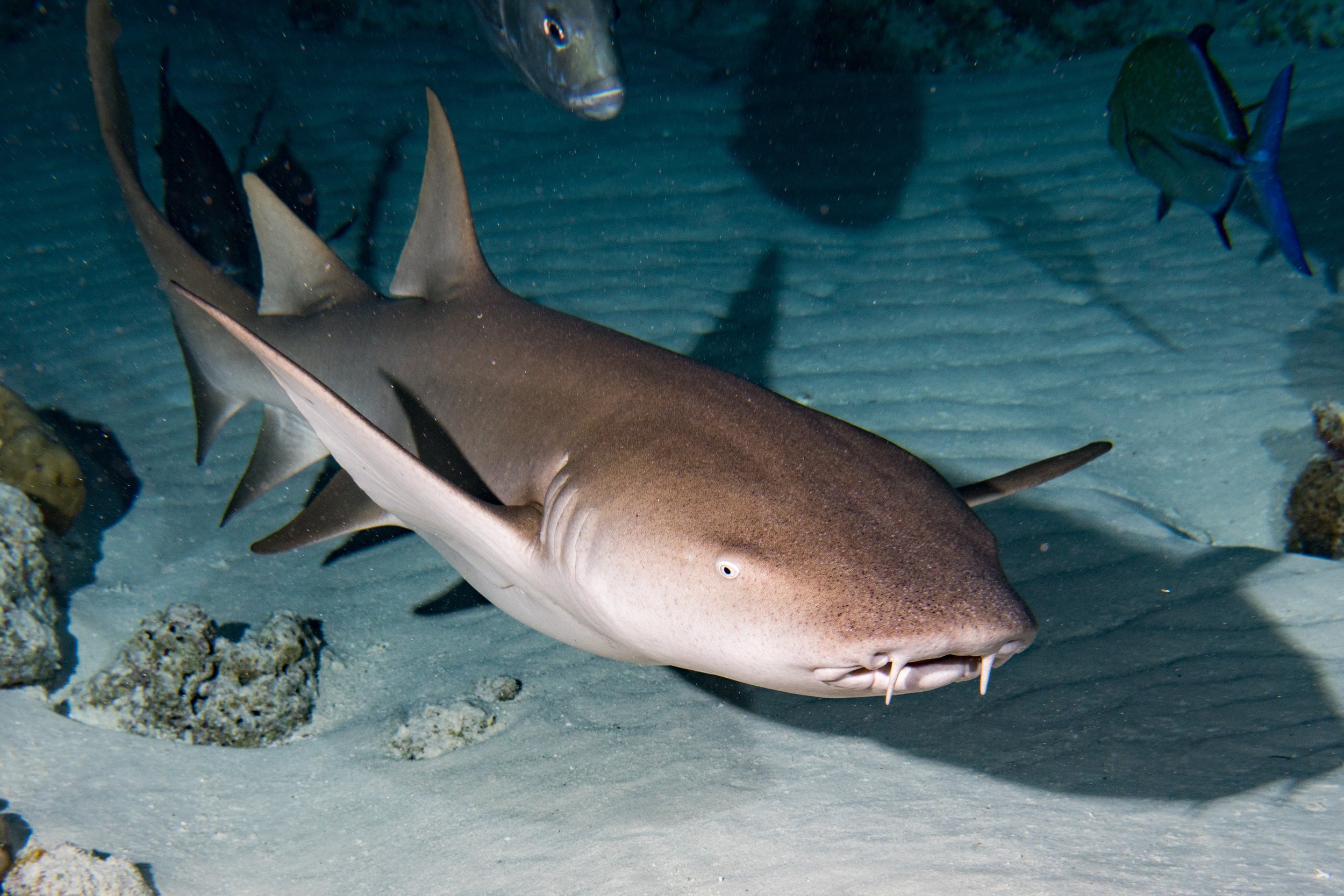

Nurse Shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum)

Nurse sharks are another popular aquarium fish due to their slow moving and adaptable nature. They are robust and able to tolerate capture, handling, and tagging extremely well. But they are ranked fourth in documented shark bites on humans, likely due to incautious behavior by divers on account of the nurse shark's slow, sedentary nature.

Distribution: East Pacific and East & West Atlantic. Locally from Rhode Island to Brazil including Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. This shark is rare north of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.

Habitat: Coastal. Bottom dwelling. Young in very shallow water, adults in deeper water.

Behavior: Nocturnal. A social shark that often rests in groups by day in shallow waters.

Migration: Unknown. Nurse sharks show strong site fidelity (typical of reef sharks), and it is one of the few shark species known to exhibit mating site fidelity, as they will return to the same breeding grounds time and time again.

Reproduction: Ovoviviparous. producing young by means of eggs that are hatched within the body of the pregnant female. The mating cycle is biennial, taking 18 months for the female's ovaries to produce another batch of eggs. The mating season runs from late June to the end of July, with a gestation period of six months and a typical litter of 21–29 pups.

Size: Born about an inch long. Maximum adult length is currently documented as 10.1 feet.

Notes: Nurse sharks are typically solitary and nocturnal animals, rifling through bottom sediments in search of food at night. They can also often be gregarious during the day forming large sedentary groups. They are opportunistic predators that feed primarily on small fish (e.g. stingrays) and some invertebrates (e.g. crustaceans and molluscs). Nurse sharks are obligate suction feeders capable of generating suction forces that are among the highest recorded for any aquatic vertebrate.

Chain Catshark (Scyliorhinus retifer)

This species is common in the Northwest Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean. It is harmless and is rarely encountered by humans.

Distribution: Northwest Atlantic from Georges Bank Massachusetts to the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea.

Habitat: Outer Continental shelf and upper slope from 118 to 2,461 feet.

Behavior: Sluggish shark often found resting on the bottom.

Chain Catsharks egg case. Image from Vineyard Gazette.

Migration: Unknown.

Reproduction: Oviparous reproduction. The female chain catshark is able to store sperm and lay eggs several days after initial copulation. The shark has been known to store sperm up to 843 days although, there are some circumstances of poor egg development in eggs laid later.

Size: The maximum length of this shark is 1.94 feet.

Notes: The chain catshark is a popular cold-water aquarium fish. Research in shark behavior, including reproduction, has been done in chain catsharks that have been kept in public aquariums or laboratories.

Chain Catshark egg case found on the wrack line on a beach in Martha’s Vineyard, MA. Image from The Vineyard Gazettte.

Tiger Shark (Galeocerdo cuvier)

The tiger shark is a solitary, mostly nocturnal hunter. It is notable for having the widest food spectrum of all sharks, with a range of prey that includes crustaceans, fish, seals, birds, squid, sea turtles, dolphins, and even other smaller sharks. It also has a reputation as a "garbage eater,” consuming a variety of inedible, man-made objects, such as vehicle license plates, that linger in the stomach.

Distribution: Worldwide. Temperate and tropical waters. Locally from Cape Cod to Uruguay including Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea.

Habitat: Coastal waters to Continental shelf.

Behavior: Strong swimmers. The tiger shark is second only to the great white in recorded fatal attacks on humans.

Reproduction: The only ovoviviparous carcharhinid. Females mate once every three years. Mating in the Northern Hemisphere generally takes place between March and May, with birth between April and June the following year.

Size: A newborn is generally 20 to 30 inches long. Males reach sexual maturity at 7.5 to 9.5 feet and females at 8.2 to 11.5 feet.

Notes: The tiger shark is captured and killed for its fins, flesh, and liver. They are considered a near threatened speciesdue to excessive finning and fishing by humans according to International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Bull Shark (Carcharhinus leucas)

Bull sharks are the only wide-ranging shark that penetrates far into fresh waters. They have been known to travel up the Mississippi River as far as Alton, Illinois, about 700 miles from the ocean.

Distribution: World-wide. Tropical and sub-tropical waters. Locally from Long Island to Brazil including the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. A rare fish north of Delaware Bay.

Habitat: Mostly shallow coastal waters, often enters far into river and fresh water. The bull shark is diadromous, meaning it can swim between salt and fresh water.

Behavior: A slow moving shark. The name "bull shark" comes from the shark's stocky shape, broad, flat snout, and aggressive, unpredictable behavior.

Migration: Migratory with changing water temperatures.

Reproduction: Viviparous. Bull sharks mate during late summer and early autumn, often in freshwater or in the brackish water of river mouths. After gestating for 12 months, a bull shark may give birth to 1 to 13 live young.

Size: The young are about 27.6 inches at birth. Adult female bull sharks average 7.9 feet long. Adult male averages 7.4 feet. Maximum size is 11 feet.

Notes: One or more bull sharks may have been responsible for the notorious Jersey Shore shark attacks of 1916. The speculation of bull sharks possibly being responsible is based on two fatal bites occurring in brackish waters of Matawan Creek.

Blue shark (Prionace glauca)

The blue shark is often seen cruising slowly at the surface. It feeds on relatively small prey, especially squid and bony fishes, though other invertebrates, small sharks, and mammalian carrion is readily taken and seabirds occasionally are caught at the surface of the water. Squid are a very important prey of the blue shark and some species form huge breeding aggregations, which are attended by blue sharks. Much of the prey of the blue shark is pelagic, though bottom fishes and invertebrates figure in its diet also.

Appearance:

Blue sharks have a slender, streamlined body with a long, pointed snout, and long, pointed pectoral fins.

Coloration:

They are typically a deep blue on their dorsal side, fading to a white belly.

Size:

They can grow up to 13 feet (383 cm) in length and weigh up to 528 pounds (240 kg).

Habitat:

They are pelagic sharks, meaning they live in the open ocean, and are found in tropical and temperate waters.

Diet:

They are primarily predators, feeding on pelagic fish, squid, and other marine animals.

Reproduction:

Blue sharks are viviparous, meaning they give birth to live young, with litter sizes ranging from 1 to 68 pups (average 34). The gestation period is from 9 to 12 months, and possible maximum longevity is around 20 years.

Distribution and Migration:

Global Distribution:

Blue sharks are one of the most widely distributed shark species, found in all major oceans.

Migration:

They are highly migratory, undertaking long journeys across oceans, often linked to reproductive cycles and food availability.

Oceanographic Influences:

Their distribution is influenced by seasonal variations in water temperature, reproductive cycles, and the availability of food resources.

Conservation Status:

Near Threatened:

The blue shark is classified as "Near Threatened" by the IUCN, due to overfishing and other threats.

Fishing Pressure:

They are a common target in global fisheries, both as a bycatch and as a target species, contributing to their vulnerability.

Shark Fin Trade:

They are a significant component of the international shark fin trade, with an estimated 20 million blue sharks killed annually for their fins.

Ecosystem Role:

Top Predator:

Blue sharks are top-level predators, playing a crucial role in regulating prey populations in the marine pelagic environment.

Symbiotic Relationships:

They have symbiotic relationships with pilotfish, which clean their teeth and gills, and with various copepods and parasites

Predators: Killer whales, larger sharks like tiger sharks and great white sharks.

Dusky Shark (Carcharhinus obscurus)

The dusky shark is highly valued by commercial fisheries for its fins, used in shark fin soup, and for its meat, skin, and liver oil. It is also esteemed by recreational fishers. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed this species as Endangered worldwide and Vulnerable off the eastern United States, where populations have dropped to 15–20% of 1970s levels.

Distribution: Probably World-wide. Tropical and warm temperate waters. Locally from Cape Cod to Florida including the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea.

Habitat: Continental shelf waters to outer shelf to oceanic waters. Avoids estuaries. Often seen offshore following ships.

Behavior: Adult dusky sharks have a broad and varied diet, consisting mostly of bony fishes, sharks and rays, and cephalopods, but also occasionally crustaceans, sea stars, bryozoans, sea turtles, marine mammals, carrion, and garbage.

Migration: Strongly migratory with changing water temperatures.

Reproduction: Viviparous. Adult females bear litters of 3–14 young after a gestation period of 22–24 months, after which there is a year of rest before they become pregnant again. Females are capable of storing sperm for long periods, as their encounters with suitable mates may be few and far between due to their nomadic lifestyle and low overall abundance. Dusky sharks are one of the slowest-growing and latest-maturing sharks, not reaching adulthood until around 20 years of age.

Size: At birth, about a length of 27.6-39.3 inches. Adult dusky sharks have a total length of at least 11.8 feet to possibly to 13.8 feet.

Notes: The range of the dusky shark extends worldwide. Records of dusky sharks from the northeastern and eastern central Atlantic Ocean, and around tropical islands, may in fact be of Galapagos shark stocks.

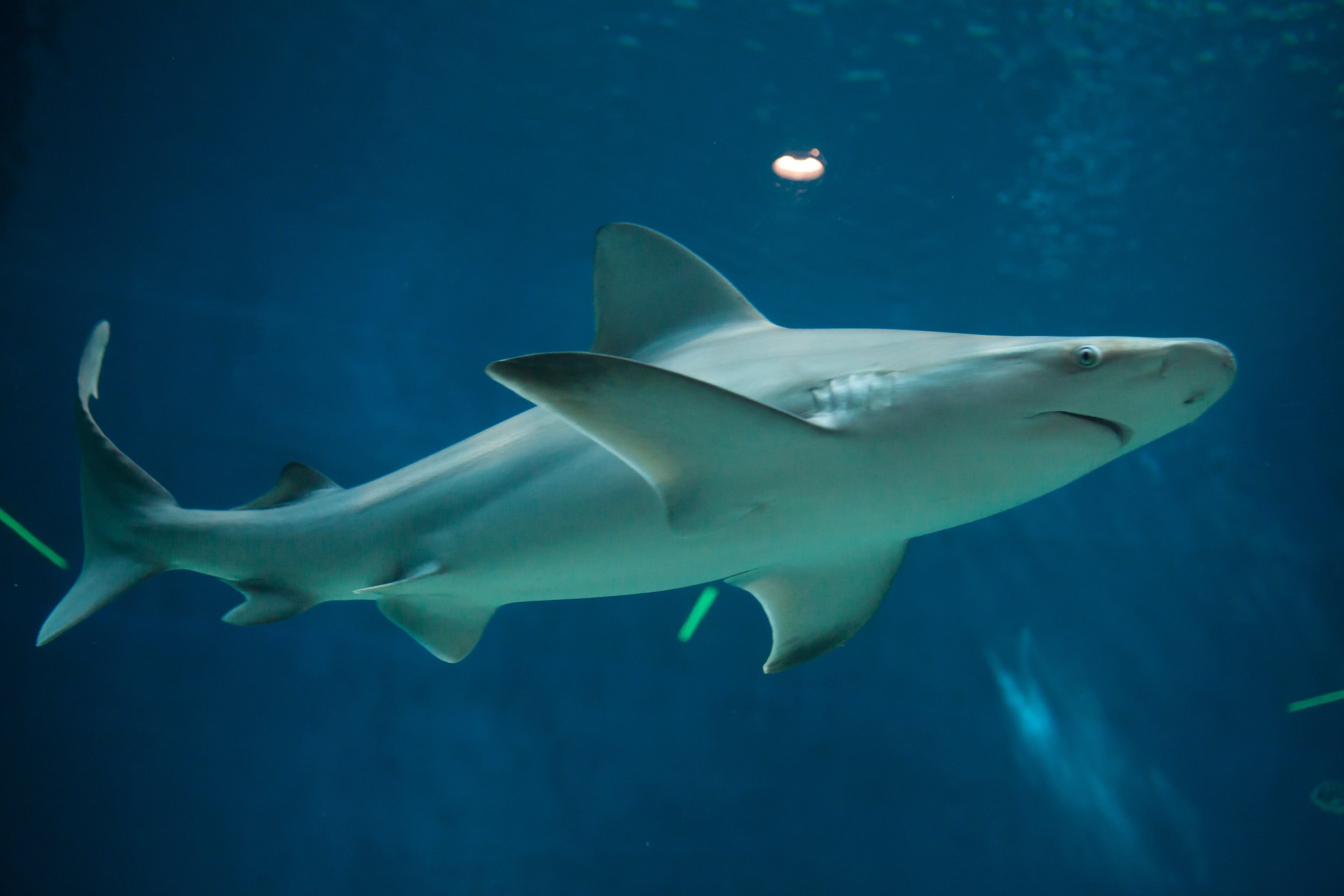

Sandbar or Brown Shark (Carcharhinus plumbeus)

Color of this shark is brownish-gray or brown above, white below. It is one of the biggest coastal sharks in the world, and is closely related to the dusky shark, the bignose shark, and the bull shark.

Distribution: World-wide. Tropical and warm temperate waters. Locally from Cape Cod to Florida including the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea.

Habitat: Mainly coastal waters including bays, harbors, river mouths, and estuarine waters. Typically from 5 to 180 feet.

Behavior: The sandbar shark preys on fish, rays, and crabs. Active more at night.

Migration: Migrates seasonally sometimes in large schools.

Reproduction: Viviparous. Females ovulate in early summer, and give birth to an average of eight pups, which they carry for 1 year before giving birth. Young form mixed-sex schools in shallow coastal nursery grounds, moving into deeper warmer waters in winter.

Size: Born 1.8 to 2.4 inches. Adult females can grow to 6.6 to 8.2 feet, males up to 5.9 feet.

Notes: In spite of their large size and similar appearance to other dangerous sharks such as bull sharks, very few, if any attacks are attributed to sandbar sharks, so they are considered not to be dangerous to people.

Scalloped Hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini)

Since 2008, the scalloped hammerhead has been on the "globally endangered" species list. In parts of the Atlantic Ocean, their populations had declined by over 95% in the past 30 years. Among the reasons for this drop are overfishing and the rise in demand for shark fins.

Distribution: World-wide, warm temperate and tropical seas. Locally from Massachusetts to Brazil including the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea.

Habitat: Coastal and offshore. Primarily in waters with temperature greater than 72 degrees F. Coastal bays and ocean waters to 900 feet.

Behavior: Scalloped hammerheads can form large schools at different stages of their life history. They can also be solitary.

Migration: Seasonally migratory.

Reproduction: Viviparous. Not much is know. The gestation period is reported to be around 12 months. Compared to other species, the scalloped hammerhead produces large litters from 20 to 50 pups, and this is most likely due to high infant mortality. Like most sharks, parental care is not seen.

Size: Born about an inch or two long. On average, males measure 4.9 to 5.9 feet. Females measure 8.2 feet with the maximum length of the scalloped hammerhead at 14 feet.

Notes: They are not considered to be dangerous to humans, and if they do harm a person it is because it’s out of surprise. This shark feeds primarily on fish such as sardines, mackerel, and herring, and occasionally they feed on cephalopods such as squid and octopus.

They are threatened by commercial fishing, mainly for the shark fin trade.

Smooth Hammerhead (Sphyrna zygaena)

Of all the hammerhead sharks, the smooth hammerhead is the species most tolerant of temperate water, and occurs worldwide to higher latitudes than any other species.

Distribution: World-wide, warm temperate and tropical seas. Locally from Nova Scotia, Canada to Florida.

Habitat: Coastal and offshore. From surface to at least 66 feet.

Behavior: Young can form large schools. They can also be solitary.

Migration: Seasonally migratory.

Reproduction: Viviparous. Females bear relatively large litters of 20–50 pups after a gestation period of 10–11 months. Birthing occurs in shallow coastal nurseries, such as Bulls Bay in North Carolina.

Size: Pups measure 20–24 inches long. Females reach maturity at 8.9 feet long and males at 6.9–8.2 feet long. Can reach sizes up to 16 feet long.

Conservation status: Vulnerable (Population decreasing)

Notes: This shark is thought to live for 20 years or more. The smooth hammerhead is potentially dangerous to humans.