Sea Turtles of New Jersey

Sea Turtles of the Jersey Shore

Graphic from NOAA Fisheries/Galveston Laboratory

Of the severn species of sea turtles that can be found around the world, at least four species can be seen along the Jersey Shore. When ocean water temperatures are in the 70-degree Fahrenheit range or higher during the summer and early fall, several species of sea turtles migrate from tropical waters to additional foraging grounds up north (including the Jersey Shore) to feed on crabs, jellies, algae, and small fish.

Often times, juvenile sea turtles are observed in the ocean and tidal estuarine waters along the Jersey Shore as they share feeding grounds with adults or perhaps discover new feeding locations on their own along a Mid-Atlantic and southern New England coastline. The leatherback sea turtle is entirely pelagic and rarely comes near shore, preferring deeper ocean waters to forage for jellies.

In Autumn, Please Watch Out for Cold-Stunned Sea Turtles!

Sea turtles are ectotherm species, which used to be called cold-blooded animals. Any animal whose regulation of body temperature depends on their surroundings or external sources, such as water, air or sunlight is ectothermic.

Sea turtles are pelagic and can normally control their body temperatures by moving between areas of water with different temperatures or basking in the sun at the water’s surface or on a beach. Yet, when water temperatures rapidly decline, usually after a strong and quick moving cold front, some sea turtles have a difficult time swimming from from shallow estuarine waters to warmer waters in the deep ocean. Sea turtles can become cold-stunned when local water temperatures drop below 55 °F (13 ºC).

Sea turtles can suffer from a form of hypothermia or cold stunning. When exposed to cold temperatures for an extended period of time, sea turtles will exhibit a hypothermic reaction that may include a lower heart rate, decreased circulation and lethargy, followed by shock, pneumonia and even death. If a sea turtle becomes cold stunned there is little chance of survival without assistance.

Some sea turtle species in our area are especially vulnerable to cold stunning including the kemp’s ridley as they are normally accustomed to warm temperate waters in the Gulf of Mexico.

NOAA officials urged any beachgoer who finds a stunned sea turtle to report the animal (see below), move it gently to an area above the high tide line, and to cover it lightly with seaweed.

WHO DO YOU CALL FOR HELP!

If you see a sea turtle that appears cold-stunned, injured, entangled, sick, dead, or being harassed by a person, in New Jersey call Sea Turtle Recovery at the Turtle Back Zoo in Essex County, NJ at 973-731-5800 x290.

In New York City, call the Riverhead Foundation for Marine Research and Preservation at 631-369-9829.

These two organizations have the authority to help stranded or sick sea turtles. Wildlife experts with the help of trained volunteers will determine if an animal is in need of medical attention, needs to be moved from a populated area, or just needs time to rest.

If you discover a sick, injured, stranded or dead sea turtle in another state, please contact your local stranding center. Information can be found here.

SEA TURTLE FIELD GUIDE FOR THE JERSEY SHORE

Atlantic Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta)

The most common sea turtle spotted along the nearshore waters of the Jersey Shore during the summer and early fall. Summer foraging range in the Northwestern Atlantic Ocean extends throughout the Gulf of Mexico and up north to Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and sometimes as far north as Newfoundland.

Size: Most adult female loggerheads have a shell length of 31 to 43 inches. Adult males are shorter than females.

Body & Color: Broad, large head, with heavy strong jaws for crushing prey. Carapace is heart shaped. Front flippers are short and thick with 2 claws, while the rear flippers can have 2 or 3 claws. Carapace and head is often a yellow-orange to a reddish-brown with a yellowish-brown plastron. The carapace is also usually covered by barnacles and other aquatic organisms.

Average life span: Perhaps to 50 years or more.

Distribution: Pelagic, but adults and juveniles can inhabit both the continental shelf to coastal waters including estuarine waters. Summer foraging range along the western North Atlantic population can extend throughout the Gulf of Mexico and along the Atlantic coast northward to Cape Cod, Massachusetts and sometimes as far north as Nova Scotia.

The majority of the world’s loggerheads nest in only two places: 1. the southeastern United States, on beaches from North Carolina through southwest Florida; and 2. in Oman, a country on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, especially on Masirah Island, an island off the east coast of mainland Oman in the Arabian Sea. Females migrate to nesting beaches every two to four years.

Diet: Primarily benthic feeders on crustaceans, including hermit crabs, spider crabs, blue-claw crabs, horseshoe crabs, and mollusks including whelks and conchs and bivalves. They ill also eat various species of jellies, sea squirts, sea cucumbers, and anemones. When available, loggerheads will eat fish (bycatch) that was originally caught in nets, but dumped overboard. Unfortunately, this type of foraging can cause loggerheads to be captured in nets and drown as bycatch themselves.

Conservation Status: Although the loggerhead is the most common sea turtle along the Jersey Shore, in other locations around the world this sea turtle is rare and in extreme decline.

The northwestern population is listed as Threatened in the United States and Canada, but are considered to be endangered within Northwest Atlantic, Mediterranean Sea, North Indian Ocean, and Pacific Ocean. The species is officially protected from harvest in Mexico, Cuba, Bermuda, and The Bahamas.

Threats: The greatest threat to loggerheads along the Jersey Shore is from boat collisions. Globally, the greatest known mortality is entanglement in commercial fishing gear, especially shrimp trawling boats. Tens of thousands of loggerheads die each after being accidentally captured and drowned in commercial fishing nets and gear.

Threats to eggs and hatchlings include degradation of nesting beach from coastal development and erosion, and artificial lighting, which can cause them to move away from the sea. This disorientation due to light pollution can lead to death of hatchlings from exhaustion, dehydration and predation.

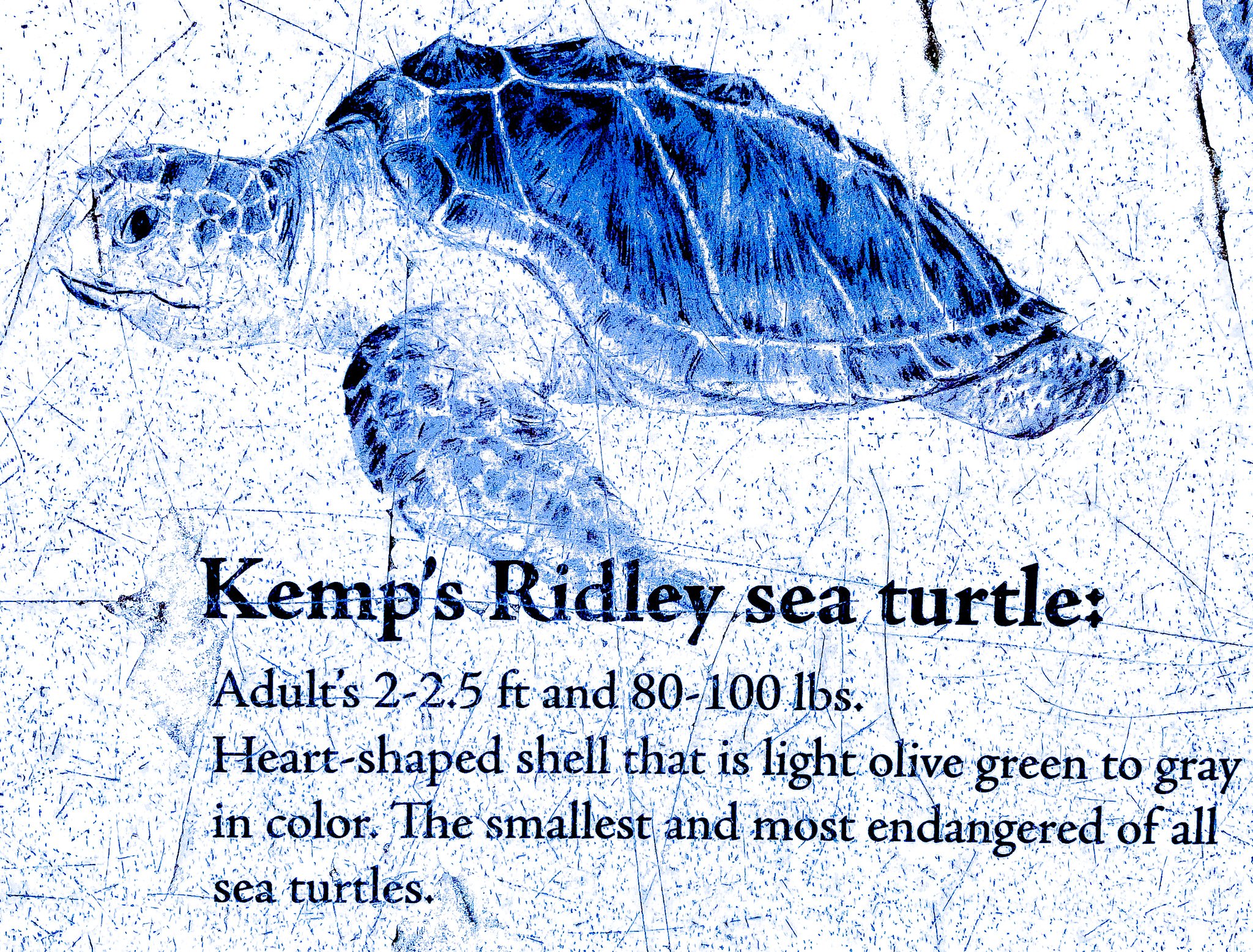

Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle (Lepidochelys kempii); also known as the Atlantic ridley sea turtle.

Kemp’s ridley are the second most common sea turtle spotted along the Jersey Shore during the summer and early fall. Kemp’s ridleys are also the smallest and most critically endangered sea turtle species in the world. Its common name comes from Richard Moore Kemp, a Key West, Floridian fisherman and naturalist who first submitted this sea turtle for identification in 1880 to Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Size: Smallest sea turtle, often reaching the weight of a large dog, about 100 pounds. Adult shell is about 2 feet long.

Body & Color: Carapace is heart-shaped. The head is triangular wit cusped parrot-like beak. The carapace is often wider that long in larger turtles. The turtle’s coloration is light gray to light olive above and yellowish cream to white underneath. One claw on each forelimb.

Average Life span: No one knows exactly how long Kemp's ridley’s live, but like other sea turtles, they are likely long-lived, estimates of lifespan are on the order of 30 years minimally, and perhaps as much as 50 years.

Habitat: Most kemp’s ridleys swim in the Gulf of Mexico, but significant numbers of ridleys in the summer forage as far north as Cape Cod Bay, Massachusetts in bays and sounds. These Atlantic coast ridleys often are juveniles foraging for food and will return to the Gulf of Mexico as coastal waters cool in fall. Records of ridleys seen in the eastern Atlantic are rare.

Most nesting takes place along Tamaulipas and Veracruz coasts of Mexico, and along the coastline of southern Texas, especially at Padre Island National Seashore. Females often nest in synchronized emergences, known as arribadas or arribazones (Spanish for “arrivals”), primarily during daylight hours, and usually on days with strong onshore winds from the northeast. Females migrate to nesting beaches every one to three years.

Diet: They have powerful jaws to eat crabs including blue-claw crabs, spider crabs, horseshoe crabs, but also shrimp, squid, sea urchins, mollusks, and various species of jellies; and slower fishes such as sea horses. Fish from bycatch is also a component of their diet, which causes the turtles to become entangled in nets and drown.

Status: Listed as Endangered (in danger of extinction within the foreseeable future) in 1970 under the U.S. Endangered Species Act; and is listed as Critically Endangered (facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future) by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. The species is officially protected from harvest in Mexico, Cuba and The Bahamas.

Threats: Their current population is a fraction of the population recorded in the 1940’s. In 1963, using a film made in 1947 by the an amateur cameraman. Archie Carr and Henry Hildebrand estimated that on the day the film was made, 40,000 Kemp's ridley females nested on a single beach in northeastern Mexico.

The greatest threat today to the Kemp’s ridley is from human use activities including collection of eggs and killing adults and juveniles for meat and other products in the United States and Mexico. Entanglement in fishing gear also poses a major threat for this species. Bottom trawling, longline, and gillnet fisheries are responsible for a large number of deaths every year. A major threat to the Kemp's ridley continues to be death by drowning in shrimp nets. Between 500 to 5,000 are killed in this way each year.

Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea)

The leatherback is mostly a pelagic species that rarely comes close to the coastline of New Jersey, but occasionally one or two will be spotted entering a shallow bay or river in search of food during the summer or fall. The leatherback’s name comes from its unique shell, which is not bony. Instead the shell is composed of a thin layer of tough rubbery skin, strengthened by many tiny bone plates that appear “leathery.” The leatherback is the only sea turtle that lacks a hard shell. This design allows the turtle’s body to contract better than a hard-shelled sea turtle when it dives to depths of over 3,000 feet in search of jellyfish. The leatherback is also the largest sea turtle in the world - averaging 6 feet in length and 500 to 1,500 pounds.

Size: The largest sea turtle currently in the world. It averages 4 to 6 feet. The largest and heaviest leatherback ever recorded was almost 10 feet and weighed 2,019 pounds. It washed ashore on Harlech beach in Wales during September 1988. Unfortunately, the turtle was found dead and had drowned after being trapped by commercial fishing lines. It was approximately 100 years old when it died. Remains of the turtle are currently on display at the National Museum Cardiff in Cardiff, Wales.

Body & Color: The body is barrel-shaped into a streamlined teardrop. The head is large and triangular; and the mouth has a weak beak with two cusps on the upper jaw to help with grasping slippery jellyfish as food. The shell is mostly black with pinkish white spots on the underside. This sea turtle also has pink and white spots on its head. Some research suggests that no two pink spots are the same shape. It’s back flippers are paddle shaped. A leatherback’s front flippers lack claws and scales and are elongated compared to other sea turtle species.

Average Life Span: Leatherbacks reach maturity at approximately 16 years old. Their average lifespan is unknown, but it's thought to be at least 30 years.

Habitat: Highly pelagic. Leatherbacks have the broadest distribution of any reptile in the world. They are also remarkable among reptiles in that they can survive in cold waters from subarctic to the subantarctic, and have been reported as far north in coastal waters off Norway and south off the coasts of Chile and New Zealand during the summer. This existence in colder water is possible due to the leatherback’s ability to keep their body temperature warmer than the water surrounding them from a thick, oily, fat layer under their skin and their ability to turn off blood-flow away from potential cold flippers. All other sea turtles species are restricted to warmer waters.

Leatherbacks forage in both deep oceanic waters and shallow waters near coastlines. Adults are known to make seasonal migrations across the Atlantic in search of food sometimes following the Gulf Stream.

Females migrate to nesting beaches every two to three years. Peak nesting areas are in the east coast of Florida, with about 50 percent of leatherback nesting taking place in Palm Beach County from March through July. Las Baulas National Marine Park, in Guanacaste, Costa Rica is another leatherback nesting hot spot. Nesting in Puerto Rico and St. Croix in the Virgin Islands continues to increase.

Diet: Lives primarily on a diet of clear, watery jellies and jellyfish like animals including salps, comb jellies, moon jellies, lion’s mane jellies, and the Portuguese man-o-war. In order to survive on just eating jellies, the leatherback must eat a lot. Juvenile leatherbacks kept briefly in captivity were able to survive by eating twice their weight a day in jellies. Apparently, leatherbacks have acquired a tolerance for a jellyfish’s sting, which can often be painful and sometimes deadly for humans.

Status: Highly endangered. Listed as Vulnerable in 2013 (facing a high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future) by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. According to NOAA Fisheries, it is estimated that the global population has declined 40 percent over the past three generations.

Threats: Major threats in the United States include entanglement in commercial fishing nets and gear, boat collisions and mistakingly ingesting plastic bags and balloons that look like jellyfish. Leatherback turtles may die after ingesting fishing line, balloons or plastic bags, plastic pieces, and other plastic debris which they can mistake for food.

Sea turtles have also been intentionally killed for their meat and skin. This activity continues to be a serious threat to leatherbacks internationally, with adult female leatherbacks primarily killed on nesting beaches in some areas.

Threats to eggs and hatchlings include egg collection, which occurs in many countries around the world and egg harvest has been attributed to catastrophic declines in some areas including in Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu, an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean.

Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas)

The green sea turtle is rarely seen along the coast of New Jersey and is rare north of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. It prefers warmer waters containing coral reefs and seagrasses, but occasionally a juvenile or wayward adult green turtle will make its way north to the Jersey Shore during the summer. The turtle is named not for the color of its shell or body, but for the green color of fat under its shell that was eaten by early sailors.

Size: Average adult shell is about 3 feet.

Body & Color: Green turtles have a teardrop-shaped or heart-shaped shell. Unlike many adult loggerhead shells, adult green turtle shells are often un-fouled by barnacles and other small sea creatures. It is often smooth. The turtle’s body is sleek with a olive to brown shell that frequently contains a radiating or wavy patterns on scutes, especially noticeable on subadults.

Although their name suggests otherwise, green turtles are actually mostly brown in body color. The common name comes from a description of the turtle’s fatty tissue that generally has a greenish tint. The name is evidence of just how often animals first came to be known by people - as food!

All green turtles have a blunt head and their lower jaw is coarsely serrated with a sharp cusp at the tip. The upper beak is more weakly serrated. Together, the jaws make a perfect cutting instrument for seagrasses.

Average Life Span: The lifespan for green turtles is largely unknown but thought to be at least 60 to 70 years. Green turtles become sexually mature at 25 to 35 years, and some may be as old as 40 before they reproduce.

Habitat: Juveniles are pelagic, then move to feeding areas in relatively shallow to slightly deep tropical coastal waters that contain seagrasses or coral reefs. Adult turtles swim in all of the world’s warm-water oceans.

In the United States, nesting green sea turtles are primarily found in the Hawaiian Islands, U.S. Pacific Island territories (Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa), Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and the East Coast of Florida.

Most green turtles in the western North Atlantic region nest in southern Mexico, southern Cuba, and southeastern Florida. Peak nesting areas in Florida are south Brevard to Boward Counties. Most females migrate to nesting beaches every other year.

Western North Atlantic hatchlings are believed to grow up in coastal waters primarily off Florida, Texas, Bermuda, Cuba, Mexico, and The Bahamas. Green turtles grow very slowly. Based on growth rates of wild turtles from Florida and The Bahamas, green turtles don’t reach reproduction or maturity until 20 to 40 years after hatching.

Diet: Green turtles eat a wide variety of small slow-moving food including algae, jellies, sea grasses, crabs, and mollusks.

Status: Breeding population is listed as endangered in Florida; they are listed as “threatened” elsewhere in the world. The species is officially protected from harvest in Mexico, Cuba, Bermuda, and The Bahamas.

Threats: At one time, green turtles were believed to be one of the most common sea turtles on the planet. Today, populations are in trouble. They are exploited for their meat and eggs internationally. Degradation of nesting and feeding habitats from overdevelopment along the coast is also a major threat. As well as boat collisions, and entanglement in commercial fishing gear.

Many green sea turtle die after ingesting fishing line, balloons, plastic bags, plastic pieces, or other plastic debris which they can mistake for food. Furthermore they become entangled in this or other marine debris, such as lost or discarded fishing gear, and can be killed or seriously injured.

Fibropapillomatosis is a disease that causes tumors externally on the exposed soft tissues of green turtles and internally on vital organs. These tumors can lead to death. The disease is most prevalent in green turtles and some evidence has linked the disease prevalence to poor water quality.